When I was a little girl, I watched my family, especially my grandma Margaret, work tirelessly to organize the early restoration efforts for our tribe.

I remember how anxious she was, worrying about how they would find enough addresses and ways to inform people about the meetings where the adults would discuss the possibility of regaining federal status as a tribe.

I recall one of the earliest meetings at the Grand Ronde Library. Over time, there were countless gatherings at the Grand Ronde Elementary School, the small green building at the cemetery, and the St. Michael’s Church gym.

As kids, we were often dropped off at the St. Michael’s gym for a couple of hours of roller skating on a Friday night, while the parents could most likely be found at Fort Hill. Those old skates had seen better days, and I was convinced my grandma had worn the same pair as a kid. I can almost still smell the stale leather and hear the clunking of the metal wheels on the wood floor. And then there were so many potlucks—where everyone would bring food to share. These gatherings were about eating together and cake walks and raffles to raise gas money for trips to important meetings with other tribes and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

I didn’t always understand why we had to attend many meetings or powwows. I’d get frustrated sometimes and complain, asking why we had to go again. That’s when my grandma would sit me down and tell me stories about how our tribal people were moved from their homelands throughout western Oregon to the Grand Ronde area. She explained how treaties had been signed, with our ancestors giving up their lands in exchange for the promise that the government would provide for the tribes on the reservation. She told me the government kept their promise for a while—until they didn’t—and then they terminated the tribes’ federal recognition.

This all happened around the same time my grandma finished high school. She had been preparing for post-secondary school when the government terminated the tribe. In a matter of weeks, she went from being recognized as an Indian to being told she was not an Indian anymore. Suddenly, they were encouraged to speak English and told they were now just “regular Americans.” Her scholarship, which she had due to her minority status, disappeared with that termination, and she never got the chance to go to school. I can only imagine how confusing and painful that must have been for her.

I’ll never forget one of those long drives to another meeting when I asked my grandma, “Why do we have to go again?” She turned to me and said, “Imagine a day when our tribal people don’t have to worry about having enough money to go to the doctor. A day when our elders will have glasses to see, hearing aids to hear, and every youngster will have the chance to go to college.” And because she knew I had been wishing for braces to fix my crooked teeth, she smiled, “Maybe one day, you’ll even be able to get your teeth fixed.” That thought made me so happy. I now ponder whether the idea of something as simple as straight teeth helped me understand the bigger picture of what she was fighting for.

Looking back now, I realize that those meetings and those sacrifices weren’t just about our immediate struggles—they were about building a future where our tribe could thrive again. My grandma’s vision wasn’t just for herself but for all tribal members and the generations to come. She taught me that the restoration of our tribe wasn’t just about recognition, it was about reclaiming our identity, our rights, and our future.

Spirit Mountain Casino

As Spirit Mountain Casino family employees, we must understand and appreciate the history and culture of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde (CTGR), whose heritage is central to our organization and community. One of the most significant days in CTGR’s history is Restoration Day, which we observe annually on November 22. This day marks the Tribe’s return to federal recognition and the restoration of its sovereign rights.

What is Restoration Day?

Restoration Day celebrates the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde’s return to federal recognition in 1983, following three decades of being wrongfully terminated by the U.S. government. The Termination Era of the 1950s saw many Native American tribes across the country lose their federal status, land, and legal recognition of their sovereignty. For the tribal people, this termination was devastating.

Why Was CTGR Terminated?

In 1954, during a period of national policy aimed at assimilating Native Americans into mainstream society, the U.S. government passed the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act. This act ended the federal recognition of the Grand Ronde Tribe, dissolved its reservation, and stripped tribal members of their land and resources. The government believed this policy would “free” Native Americans from dependency, but instead, it led to the collapse of community structures, severe poverty, and disconnection from traditional lands.

The Path to Restoration

Restoration didn’t happen by chance; it resulted from a determined effort by visionaries like Margaret Provost, Marvin Kimsey, and Merle Holmes. They started organizing efforts in the community in the 1970s, convinced that with persistence and unity, the Tribe could regain federal recognition.

My grandma was a guiding force, determinedly working to unite our tribal people. She knew that the future of the Grand Ronde people depended on this fight. Marvin Kimsey, who would later become Tribal Chairman, and Merle Holmes played critical roles in legal and organizational efforts, lobbying local, state, and federal governments and contacting other Native communities. Together, through countless meetings, petitions, and unwavering dedication, they gained momentum.

Today, a statue of Margaret Provost, Marvin Kimsey, and Merle Holmes stands outside the Tribal Governance Center, a tribute to their sacrifice and vision for a brighter future for the Grand Ronde people. Their legacy is hope and resilience, ensuring our Tribe will be recognized and thrive again.

Many people played pivotal roles in restoring the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde—far too many to name here. But these three stood out for their unwavering belief in something greater than themselves: a vision for the future of our tribe for generations yet to come.

Restoration in 1983

Efforts culminated on November 22, 1983, when the U.S. Congress passed the Grand Ronde Restoration Act, officially restoring the Tribe’s federal recognition. This victory was a testament to the resilience of the Grand Ronde people. Restoration restored our sovereign rights and laid the foundation for rebuilding our economy, culture, and community, including the creation of Spirit Mountain Casino, which helps support tribal programs today.

Why Restoration Day Matters

Restoration Day is a powerful reminder of what we can achieve through persistence and community. It’s a time to honor the visionaries who led the restoration effort and to celebrate the return of our people’s rightful place among sovereign tribes.

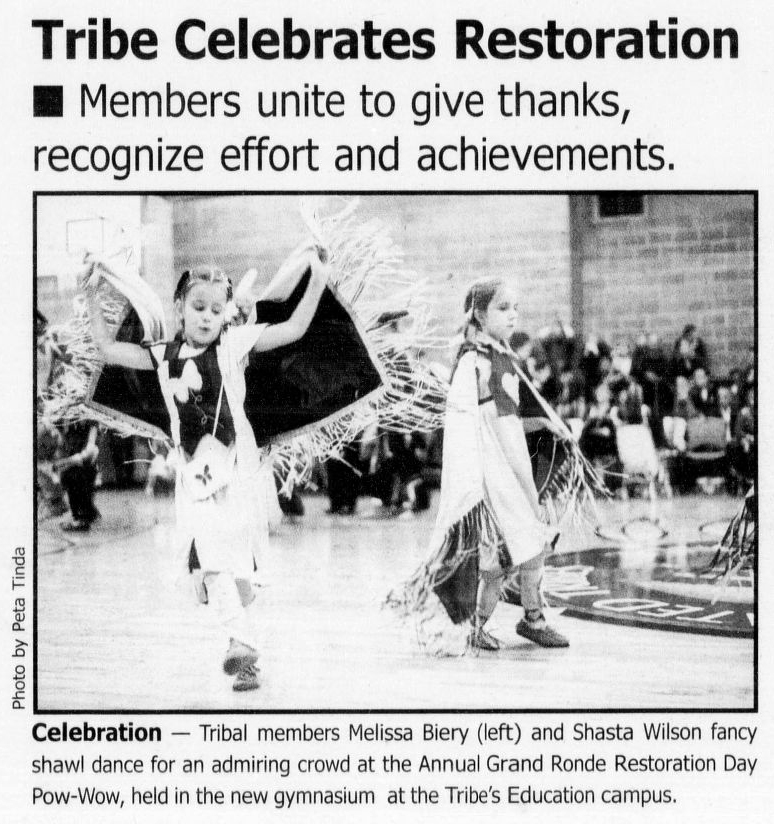

This year, the tribe will celebrate Restoration Day in the Event Center at Spirit Mountain Casino on Friday, November 22, and host a Pow Wow on Saturday, November 23, in the same location.

Thank you for taking the time to read this and for understanding the importance of this Restoration Day.

Sincerely,

Camille

photo of Visionaries statue by Michelle Alaimo/Smoke Signalz